Everybody is unequal

Health inequality: why the poor die earlier

The poor die ten years earlier than the rich. Social status is one of the strongest determinants of health quality – this is universally true. Public health researchers take a look at how inequality is leading to bad health, and what we could do about it.

What does a worker in a Finnish fish factory, a German nurse and a bus driver in Portugal have in common? All of them are sick more often and will die sooner than their countrymen who are professionally and financially better off. Since the 1970’s, this imbalance has become more pronounced throughout Europe. Back then, Englishmen died on the average five and a half years earlier than their upper-class counterparts. In the 90’s the difference was nine and a half years. The results are similar for Germany. Sir Michael Marmot is convinced that “When we continue along the same path that we have taken up to now, the gap will not shrink.” The Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at the University College Medical School, London is one of the leading experts on the topic of inequalities in health and their causes, and chairs the World Health Organisation’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health (see interview at the end of the text).

The disparity threads its way through every social group. A study conducted in Germany by the Hans Böckler Foundation has shown that on retiring, a high-level civil servant will live up to five years longer than a colleague coming from a lower rank. “Between the lowest and highest income levels in Germany, there is a gap in the life expectancy of up to ten years,” states Professor Rolf Rosenbrock of the Social Science Research Center in Berlin. “This is such an unpleasant truth, that politicians and the media would much rather ignore it.”

Whereas other European countries have a history of researching how to lessen the disparity in health quality between the various income groups, Germany lacks the basics. As opposed to most European countries, Germany does not have a central data bank for the collection of data concerning the occupation and cause of death of the dead.

Michael Marmot says that, “Germany shies away from compiling the necessary data into a central data bank because of its past.” Thus German studies must rely on spot tests. The most important basic data is the micro-census, a survey of 400,000 randomly chosen households. In addition, there have been infrequent examinations of the health and retirement insurance statistics, and since 1984, there has been a survey periodically performed by the social-economic panel of the German Scientific Research Institute. Compared internationally, Germany sticks out primarily because of the lack of data. When it is able to come up with data, however, then its research results are on a par with the rest of Europe.

No European role model

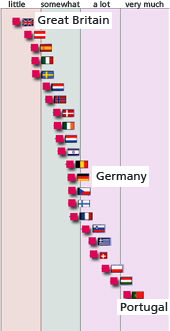

The relative placement of a particular nation within any socio-economic study depends on which analytical aspect is featured – income, educational level, type of job, etc. For instance, in a comparison of 22 nations concerning what influence the level and type of education had on the workers’ subjective self-appraisal of their health, Germany ranked 13th. Great Britain, Austria, and Spain performed much better. The study was conducted by health expert Professor Olaf von dem Knesebeck of Germany’s Hamburg-Eppendorf University Clinic. He also found that women with lower education had twice the health problems as women with higher educations. With men the variance was one and a half times. A look at death rates also indicated no clear European model.

Since there is also no first place among European countries, there is no model for the others to copy. Von dem Knesebeck emphasizes that “It is important to have a health system that offers the equal access for everyone. But that is not nearly enough to offset the disparity between the social classes.” Besides material factors, which count for the quality of access to health care, there are other aspects that play important roles.

The end of a social dream

In 1964 the American sociologist Charles Kadushin concluded that, “…in modern Western countries the relationship between social class and the prevalence of illness is certainly decreasing and most probably no longer exists.” By the mid-1960’s there was a general assumption that socio-economic differences would soon have no more influence on disparities in health.

The 1982 Black Report, a well-known English investigation, swept away this belief. It shows that there actually is a clear relationship between socio-economic status and health. Since then social epidemiologists try to find out what effects these inequalities. Has it to do with the living and work conditions of the people in the poorer social strata, on the quality of education, the amount of cigarette or alcohol consumption, or lack of exercise? Or does stress and the lack of creative interaction in the workplace play a role? “There is no single factor that explains everything,” says Marmot. “Studies are showing that it is a combination of negative factors accumulating over a lifetime.”

Educated Smokers, rich Drinkers

Variations in smoking habits throughout the social levels play an important role in health inequalities. But the stereotypes of the blue collar worker hard at work with a cigarette dangling from his lips while the white collar manager sits at his desk thoughtfully chewing a slice of apple does not truly represent the European reality. It is true that people in the lower social strata in Norway, Denmark, England, and Germany smoke more. But in Italy and Spain there is no difference between the upper and lower classes – when it comes to smoking they are equalitarian. And better educated middle-aged women actually smoke more than their lesser educated counterparts.

However, the number of traditional industrial jobs is shrinking. In Germany, for instance, every five years a million “blue collar” jobs are lost. Instead of physical stress, psychological stress is becoming more and more a factor. “My work is making me sick” – for every fourth worker in Germany, this statement is now true. This is also the average in West European countries; the Finns and the Swedes have a much stronger sense of pressure in the work place than the average European worker. Those who continually feel the time and energy they invest into their profession doesn´t match the recognition they receive, may well suffer physically and psychologically. The risk of coronary heart disease increases one and a half to six fold, depending on the study cited. This can affect bus drivers as well as the bus company’s manager. In general, the more control a worker has on his or her working conditions the healthier the worker is likely to be.

On the other hand, conditions in the workplace have become more important factors. In every European country, people who are involved with heavy manual labor have more health issues than those who have desk jobs. This is primarily accounted for by the work conditions that existed up until the end of the 1980’s, for example working with products containing cancer-causing materials such as asbestos and lacquers.

There is a similar situation with the drinkers. No social group is immune to alcohol abuse. In Germany, it affects every social class; in Sweden those with more money are more likely to suffer from alcohol addiction. Rolf Rosenbrock stresses that, “Difference in behavior is responsible for much less than half of the inequality in health.” Scientists suspect that such behavioral tendencies as smoking, drinking, and the lack of exercise are on the decrease as influences on health inequalities.

Grabbing for a cigarette is often a manifestation of unfavorable living conditions. “To make it easier for people to make healthy life choices, you have to influence their living conditions,” acknowledged Olaf von dem Knesebeck. “However, this is much more complicated than for the doctor to simply tell the patient; ‘Stop smoking – it’s bad for you!’

Unhealthy Birthmark

The European Science Foundation’s program “Social Variations in Health Expectancy” is concerned with studying the influence of a person’s socio-economic background and upbringing on his or her health. The conclusion: the childhood environment has a major influence on a person’s health in adulthood. Disadvantaged children will have more health problems as adults.

The British have access to the most comprehensive collection of data on this theme. Since 1946 they have been systematically following the health of a group of people who were all born within the same week. Three major studies containing around 17,000 participants have been conducted so far. The latest analysis revealed that the babies born in 1946 who grew up in deprived surroundings were in poorer health at the age of 53 than those who had grown up in affluent families. This relationship remained true even after the subject’s social position in adulthood was factored in. Tell me who your father is and I’ll tell you how healthy you are.

Equal Opportunity instead of More Medicine

But how to overcome the inequality? In the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, US-american health expert Dr. Lisa Berkman of Harvard University draws this conclusion: classic medical intervention is not particularly helpful. Strategies are needed that lessen social inequalities. These include a more equal distribution of income, earlier, more, and better quality education, and easier access to top-level health care. All areas in which most European countries have not excelled in the last years.

—

Interview with Prof. Michael Marmot

Michael Marmot is Chair of the global Commission on Social Determinants of Health of the World Health Organisation. He is also Director of the International Centre for Health and Society, and Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at the University College London. Professor Marmot has been at the forefront of research into health inequalities for the past 20 years, as Principal Investigator of the Whitehall studies of British civil servants, investigating explanations for the striking inverse social gradient in morbidity and mortality.

The poor live shorter and suffer from more diseases than the rich – everywhere in Europe. Why?

There is not just one factor, rather it is a whole complex of factors. It starts in pregnancy and early childhood and has a steadily increasing effect as one grows older. We should not fall into the danger of concentrating on only a few influences. For instance, we know that people from the lower classes smoke more and have a more unhealthy diet. This is certainly an important reason for the disparity in health, but we need to ask why these people smoke more and eat more unhealthy foods.

Where would be a good point to start a change?

We know from a lot of studies that people who feel in control over their work and life live a more healthy life. Give people more control over their work, and they get sick less often and take less absent leaves from work. Employers should not only ask, how they could make the workplace more productive. They should concentrate on getting the workforce more engaged. Give people more control over their lives and they will make healthier lifestyle decisions. The chance of success for this measure is at least higher than shaking your finger and exclaiming: Don´t smoke so much!

Yet there are only rare systematical programs on the national level. What needs to be done?

You cannot ignore what is going on in society more generally. We have an increase in income inequality, and the social mobility has been getting less. It´s harder to move up the ladder. The individual person cannot do much to change the situation. A political change is necessary. It is important to have a much stronger open public debate about this issue. We really understand a lot about inequalities in health by now. Early education and better work and life environments are very important. What is needed is a process that turns this knowledge into practical policies – on the local, regional, and national levels.

Text: Fabienne Hübener

For: Apotheken Umschau (2009)

Translation: Marty Cook

Fotos (from top to bottom): 1 (workers): olly / fotolia.de, 2 (drinker): Udo Kroener / fotolia.de, 3 (baby): foun / fotolia.de